Editor's Choice

The Poverty, Philanthropy and Social Conditions in Victorian Britain team pick some of their highlights from the collection.

The Cholera Epidemic

Emma Sudderick

Between 1831 and 1832 an outbreak of cholera in British towns and cities, beginning in Sunderland, initiated a series of epidemics across the country. By the end of the nineteenth century, the country had experienced four epidemics of the disease (1831-1832, 1848-49, 1853-54 and 1866). Squalid living conditions caused severe issues for the poor districts in major cities. Lack of sanitation, poor water treatments and tenement housing meant that the disease spread rapidly through communities.

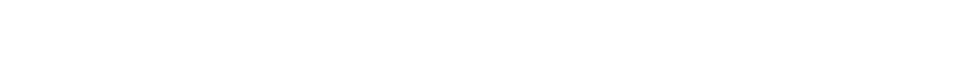

A particular highlight of the project is the original documentation from the 1850s discussing the Board of Health regulations and changes to legislation to prevent the spread of the disease across the country. In the official Poor Law correspondence from Commissioner John Walsham relating to the Eastern district of Britain there are several reports concerning the outbreak during the period, with accounts of symptoms from the medical officers and advice on preventative methods. A leaflet containing instructions issued by the Cholera Committee of the Royal College of Physicians regarding the treatment of cholera notes that "debility, exhaustion, and exposure to damp, render the poor especially subject to the violence of the disease. The Committee urge upon the rich the necessity of supplying those in need with food, fuel, and clothing". The document further stresses the importance of removing or counteracting impurities in the air, water and soil through ventilation, cleanliness and chloride solutions.

It wasn’t until the 1850s that the true cause of cholera was discovered by physician John Snow, who proposed the disease was spread by contaminated water. Prevalent theories prior to this included the ‘miasma theory’, that ‘bad air’ caused by particles of decomposing materials or poisonous vapour lead to diseases.

The outbreaks between 1831 and 1866 began investigations into sanitary conditions and medical reform, with the introduction of a Central Board of Health in 1848 following the Public Health Act. In London, the Metropolitan Sanitary Association was established in 1849 to encourage public health provision in the capital. The "removal of nuisances" was one procedure which aimed to prevent contagious diseases and in 1866 the Sanitary Act passed, making local authorities responsible for removing ‘nuisances’ and improving slum dwellings.

These documents provide a valuable insight into the impact legislation had on the workhouse administration as well as the approaches to poverty during the outbreak. You can read more about the cholera outbreak in John Walsham’s district here, including information about preventative measures and handling of symptoms.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Education and Opportunities for Women

Emma Woodcock

In the late nineteenth century, amidst a climate of social reform, opportunities for women in terms of their education and employment began to increase. Higher education institutions started to accept female students – Girton College, Cambridge opened in 1869 (as the ‘College for Women’) and was the first residential college for women, but it was not until 1878 that women could be awarded degrees as the University of London began to accept women on the same terms as men.

Much of this development was fuelled by groups of pioneering women who, if the world of higher education was not to be opened to them, were determined to forge their own path into it. Girton was founded by three women as part of their campaign for women’s educational rights. Five years later, in 1874, a group of women including Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Sophia Jex Blake established the first medical school in Britain which allowed women to both graduate and practise medicine. The collection from Senate House Library includes several documents from the London School of Medicine for Women (now the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine), such as its prospectus for 1897-1898, which outlines the School’s entrance requirements, fees, courses of study and syllabus. It also includes the School’s report for the year 1898, which lists the governing body, lecturers, financial records and numbers of women entering and qualifying from the school. Through the report it is possible to trace various prominent women’s medical careers. The Report of the Executive Council highlights how one student, Marion Hunter, “was chosen by the India Office to go to Bombay to assist in dealing with the plague outbreak” and marks the resignation of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who had been a lecturer at the School since its establishment (she continued as its Dean). The same report includes the name of Elizabeth’s daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, who qualified in 1897 and, putting her personal and professional reputation at risk, went on to become a high-profile figure in the women’s suffrage movement.

Much of this development was fuelled by groups of pioneering women who, if the world of higher education was not to be opened to them, were determined to forge their own path into it. Girton was founded by three women as part of their campaign for women’s educational rights. Five years later, in 1874, a group of women including Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Sophia Jex Blake established the first medical school in Britain which allowed women to both graduate and practise medicine. The collection from Senate House Library includes several documents from the London School of Medicine for Women (now the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine), such as its prospectus for 1897-1898, which outlines the School’s entrance requirements, fees, courses of study and syllabus. It also includes the School’s report for the year 1898, which lists the governing body, lecturers, financial records and numbers of women entering and qualifying from the school. Through the report it is possible to trace various prominent women’s medical careers. The Report of the Executive Council highlights how one student, Marion Hunter, “was chosen by the India Office to go to Bombay to assist in dealing with the plague outbreak” and marks the resignation of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who had been a lecturer at the School since its establishment (she continued as its Dean). The same report includes the name of Elizabeth’s daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, who qualified in 1897 and, putting her personal and professional reputation at risk, went on to become a high-profile figure in the women’s suffrage movement.

Further documents in the Senate House Library collection illustrate other contemporary work by women intending to widen the range of opportunities open to them and to women in poorer, more deprived areas. Throughout the nineteenth century teaching was one of the very few professions open to women. However, as a 1912 pamphlet titled 'Openings for university women other than teaching' illustrates, “recent openings and pioneer work” provided impetus for this to change. The pamphlet lists professions open to women, with the length and cost of training as well as reasonable salary expectations. In the interest of helping to improve the situation of poorer women, the Women’s University Settlement was founded in 1887 by women from Girton and Newnham Colleges, Cambridge, Lady Margaret Hall and Somerville College, Oxford, Bedford and Royal Holloway Universities. A reprinted report on the Settlement from the Newnham Letter of December 1887 details its development and how the work was being extended to further the welfare improvements for women and children in Southwark.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The New Poor Law: Administering and Classifying Poverty

Amy Hubbard

In 1834, England’s system of relief for the poor was overhauled by the Poor Law Amendment Act. A direct result of the inquiries of the Royal Commission of the Poor Laws (1832-34), the New Poor Law aimed to re-organise, regulate and monitor the administration of poor relief across the country in order to reduce the escalating costs of outdoor relief. The Poor Law Commission (later to become the Poor Law Board, and subsequently the Local Government Board) was appointed to oversee this new systemisation, and included within Poverty, Philanthropy and Social Conditions in Victorian Britain is a collection of correspondence of these governing bodies digitised from the National Archives UK.

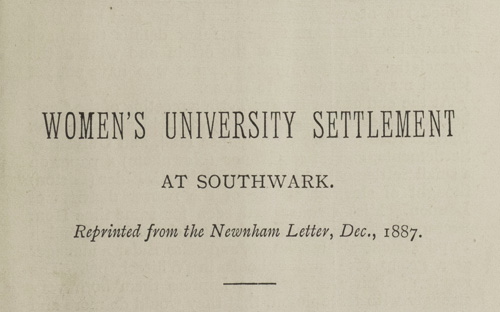

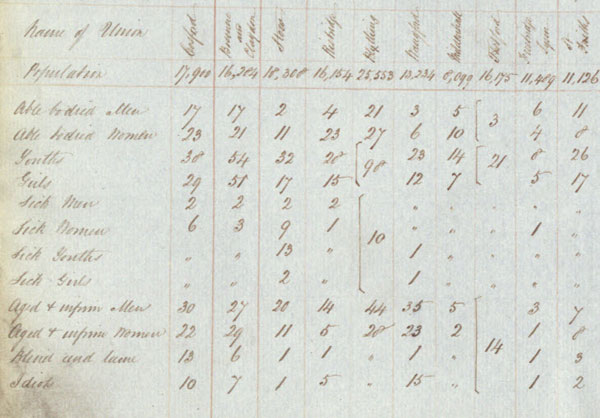

Covering the period 1834-1904, these documents offer a fascinating insight into the implementation of the new Act and its evolution as theory became subject to the reality of practice. From the Commission’s earliest correspondence, it is possible to trace the development of understandings of one of the key pillars of the new system – the classification of the poor. The correspondence and papers of James Phillips Kay-Shuttleworth, a Commissioner who oversaw the “Eastern district” including Norfolk and Suffolk, demonstrate how investigations and reports on the “inmates” of workhouses were recorded according to sex, age, physical health and disability. The workhouse occupants are further grouped by the term “able-bodied” which was largely used to identify those who were and were not capable of labour and thus of earning a living. This classification was not merely for administrative purposes; it also informed the layout and architecture of the workhouses, as can be seen in the floorplans included in the papers of Colonel A C a'Court.

As the New Poor Law became increasingly established, the classifications were expanded upon and standardised: Article 98 of the 1847 Consolidated General Order divided paupers admitted to workhouses into seven distinct classes, including divisions between the able-bodied and infirm. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, these classifications for both indoor and outdoor relief were still under scrutiny, and the possibility of further, more complex sub-divisions and definitions continued to be the subject of much debate. Classification of workhouse inmates: miscellaneous correspondence and papers dated from 1878-1895, documents the suggested classification amendments and some of the ensuing discussions.

An 1895 letter from Poor Law Inspector Henry George Kennedy responds to the suggested use of moral character as part of the indoor relief classification procedure in which paupers of good character would be afforded improved treatment:

“I am entirely opposed to graduating the character of the relief afforded to the destitute on any such system of extended investigation…I think of no body of human beings who are qualified to pronounce a verdict or demerits of so much of a man’s conduct, temptations, motives and necessities, during a period of twenty years, as they may happen to have bought to light…”.

“I am entirely opposed to graduating the character of the relief afforded to the destitute on any such system of extended investigation…I think of no body of human beings who are qualified to pronounce a verdict or demerits of so much of a man’s conduct, temptations, motives and necessities, during a period of twenty years, as they may happen to have bought to light…”.

A letter dated the same year from Poor Law Inspector Courtenay similarly highlights the difficulties in involving moral character in classification, questioning whether such judgement should be based on past or present conduct, how particularly small “country” workhouses would meet such requirements based on often limited accommodation, and how such treatment could lead to “charges of favouritism”.

Such classifications and the debates surrounding them had a significant and complex impact on nineteenth century understandings of the poor and the destitute, and on the concept of poverty as a whole. To discover more about the Poor Law Commission’s administration of poor relief from 1834-1904, click here to view documents from The National Archives UK.